Financialization of Land and Housing

Habitat International Coalition (HIC) welcomed the report on housing financialization of the UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing at the recent 34th session of the UN Human Rights Council. HIC has long been part of civil society movements heralding the danger to human rights, particularly the right to adequate housing, of the financialization of housing and land, and calling for social regulation of real estate markets internationally and locally.

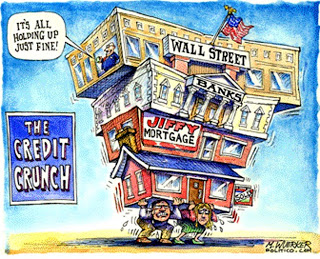

Recently, HIC and several other organisations had warned the international community—in vain—about the need to manage global market dynamics, questioning the assumption of a “self-regulating” real estate market in international frameworks and commitments such as the “New Urban Agenda” (NUA), the principal outcome document of the Habitat III conference. HIC welcomes the Special Rapporteur Leilani Farha’s further effort to address this deliberate omission in the NUA. Her focus on the hazards from the financialization of housing is consistent with HIC’s global experience, as reflected also in HIC-Latin America’s participation in public hearings before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on the impoverishing consequences of the housing market and violations of economic, social and cultural rights in precarious settlements.

Notably, private financial capital only invests in the interest of high returns for its financial stakeholders, and not social or public interest nor human rights. The re-municipalization of different services such as the distribution of water, is being carried out in different part of the world due to the negative consequences of privatizing public goods as commodities, while they already are articulated as human rights. Ms. Farha’s current report on housing financialization provides an indispensable analytical framework of state’s corresponding human rights obligations, and HIC believes that it forms a necessary starting point for achieving adequate housing and basic services for all by 2030, as the agreed Sustainable Development Goals requires.

Since the Habitat Agenda (Istanbul, 1996), and, in particular, in the context of the most recent financial crisis (2008), hundreds of millions of people in diverse economies have suffered violence, criminalization and impoverishment, while many millions have lost their homes due to housing market and finance dynamics. Governments, municipalities, communities, social organizations and socially orientated housing providers around the world are still struggling with the consequences of the previous decade’s financial crisis linked to the housing bubble. Even though, the private-homeowner and commercial mortgage-based model of housing provision has failed many, most governments continue those policies. Market-driven megaprojects, land grabbing and urban renewal typically displace people and destroy communities worldwide. Small homeowners, as well as renters and inhabitants of unauthorized housing zones are left to pay the price, while vacant housing units are sold to investments funds.

Today, some 330 million households worldwide are financially overburdened by housing costs. HIC believes that land and property must be fairly distributed and socially regulated to protect against their perversion through financialization, and that possessing property includes a duty toward society. In HIC’s collective experience, alternatives to private property in many societies (community land trusts and housing, public housing, housing cooperatives, self-managed community housing et al.) play an important role in meeting habitat needs. Such alternatives achieve “the full and progressive realization of the human right to adequate housing,” as repeatedly promised at Habitat II (1996), 30 years after that right was enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights ICESCR).

As stated in the Special Rapporteur’s report, states’ obligations concerning private investment in housing and the governance of financial markets go well beyond a traditional understanding of a duty simply to prevent private actors from actively violating rights. States should regulate and direct private market and financial actors to ensure that their actions and operative rules are consistent with human rights. In this sense, the report also echoes the ongoing discussion on implementing ICESCR in the context of business activities, which highlights housing and real estate investment as a key factor within global finance and subject of states’ human rights treaty obligations. This argues for needed transnational regulations of related markets, operationalizing the extraterritorial obligations of human rights, among the other corresponding domestic, individual and collective dimensions of states’ paramount human rights obligations.

Human rights obligations surpass national policies and legislation, and apply to all territorial and jurisdictional spheres of the state, including local authorities and governments. Nevertheless, as stated in the report, financialization as a driver of policy often makes governments accountable to profit-seeking investors at the expense of human rights. In this sense, HIC considers particularly appropriate the report focus on mechanisms to ensure also that subnational governments uphold the human right to adequate housing. Since, in democratic governance contexts, the roles of subnational and local governments can be particularly relevant to cut or counterbalance these often-symbiotic relations among political powers and financial interests.

In our age, notorious for being the greatest disparity in wealth ever recorded, inequality is found strikingly in the housing sphere. With some one billion citizens living in inadequate housing around the globe, with millions of empty homes and markets that do not respond to the greatest housing needs, urban centres are becoming the sole preserve of those with wealth. This pattern is anathema to the vision of the “right to the city” and “cities for all,” included in the NUA, and the “human rights city” presented in this Council’s Advisory Committee study of 2015.

HIC reminds that, coexisting with financialization as the dominant mode of formal housing production and management, another more-human practice far exceeds such formal solutions of private and public sectors combined—at least in numbers of housing units. The experience of socially produced habitat and, in particular, housing, is the nonmarket processes carried out under inhabitants’ initiative, management and control such that generate and/or improve adequate living spaces, housing and other elements of physical and social development. The “social production of habitat” takes place without—and often despite—impediments posed by the State or other formal structure or authority.

[For more information and cases, go to the websites of HIC Secretariat, HIC Latin America and HIC’s Housing and Land Rights Network MENA. ]

While the Habitat Agenda promised States’ and governments’ recognition of social production of housing for the past 20 years, the Habitat III process found the necessity to revive that neglected commitment to reassert the imperative of State-supported social production of housing. However, the resulting “New Urban Agenda” fell short of explicitly recognizing such beneficial collaboration between both inhabitants and States toward fulfilling the human right to adequate housing, creating job opportunities, building citizenship and community, or the need to regulate and support it. The Special Rapporteur’s recent report on financialization and its alternatives highlights what has yet to be restored to the “New Urban Agenda.”

|